This blogpost is the final one of five looking at the Transforming

Care programme through the prism of the national statistics regularly produced

by the ever excellent @NHSDigital.

The first blogpost looked at the overall number of people

with learning disabilities and autistic people identified by the statistics as

being in inpatient services.

The second blogpost looked at statistics on the number of

people being admitted to inpatient services, and where they were being admitted

from.

The third blogpost looked at when people were in inpatient

units, how far were they from home and how long were they staying in inpatient

services.

The fourth blogpost looked at planning and reviews for

people within inpatient services.

This final blogpost will focus on the number of people

leaving inpatient services (charmingly called ‘discharge’ or 'transfer') and what is

happening leading up to people leaving. Again, even if the numbers of people leaving

are not yet rapidly changing as a result of Transforming Care, the impact of the

Transforming Care programme should be visible in the number of people getting ready to

leave and how well people’s plans to do so are developing.

The first and most obvious question is whether people in

inpatient services have a planned date to leave (I will pick up on the

complications of what ‘leaving’ actually means later in this post). The graph

below shows the proportion of people in inpatient services with a planned date

for transfer, from March 2015 to September 2016 (according to Assuring

Transformation data). There was a worrying drop in the proportion of people

with a transfer date in 2016, but by September 2017 over half of people (55%)

had a planned transfer date.

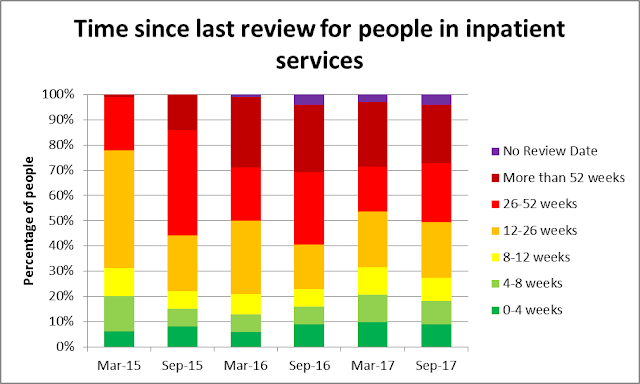

A date might be ‘planned’, but how distant in time is the

planned transfer? The 5 columns on the left of the graph below show this information

according to Assuring Transformation data, from March 2015 through to September

2017. Consistent with the earlier graph, the proportion of people without any

planned date to leave at all increased hugely in 2016, with the position

recovering throughout 2017. By September 2017, 11% of people had a planned

transfer date within the next 3 months, 16% had a planned transfer date between

3 and 6 months ahead, and 9% of people had a planned transfer date between 6

months and a year ahead. For 13% of people their planned date to leave was

between 1 and 5 years ahead, and for 7% of people their planned date to leave

was overdue.

The right hand column of the graph shows equivalent

information for August 2017 from the MHSDS dataset (see the first post in this

series for details of the two datasets), which focuses more on people with

learning disabilities and autistic people in more short-term mainstream mental

health services. Possibly because of the mainly short-term crisis nature of

people’s time in these services (in other words, people come in for a short period of time and leave again, with planned 'transfers' not part of the picture), the vast majority of people (87%) had no

planned date for transfer. The second post in this series showed that a large

proportion of ‘admissions’ to inpatient services were people transferred from

acute hospital services and readmissions (where people had previously been in an inpatient service less than a year before) – what’s happening to people in these

mainstream mental health inpatient services needs to be better understood.

So far, the statistics look like there is a push from

Transforming Care that is having an impact on the number of people with plans

to leave. Do we know anything about the plans themselves? Well, if people are

leaving the inpatient unit to go home in some sense then my expectation would

be that the person’s local council should be aware of the plan to leave. The

graph below shows information from Assuring Transformation based just on those

people with a plan to leave – for this group of people, are councils aware of

the plan? Over time, the proportion of people with a plan where their council

is aware of the plan is dropping – from over two thirds (69%) in March 2015 to

just over a half (53%) in September 2017. Just as worrying is that in September

2017, for a third of people (33%) it wasn’t known whether the council was aware

of the plan or not, a huge increase from March 2015 (7%). At the very least

this suggests that the close working between health and social care envisaged as

central to Transforming Care is not universally happening.

There are other signs too of potential haste in making plans

to leave. The Assuring Transformation statistics report whether a range of

people (the person themselves, a family member/carer, an advocate, the provider

clinical team, the local community support team, and the commissioners) have

agreed the plan to leave. For those people with a plan to leave, the graph

below reports the proportion of their plans that have been agreed by different people,

from March 2016 to September 2017. Over time, smaller proportions of plans have

been agreed by anyone and everyone potentially involved. By September 2017,

less than half of plans had been agreed by the person themselves (48%), a

family member (44%) or an advocate (48%). Only just over half of plans had been

agreed by the provider organisation (55%), the local community support team

(51%) or the commissioners (55%). Even though not everyone will be in contact with family members to agree these plans, for example, to what extent are these actually feasible

and sustainable plans that will result in a better life at home for people in

inpatient services?

The final graph in this short blogpost series is one of the

most important – how many people have actually been transferred from inpatient

services, and where have they gone? The graph below adds up monthly ‘discharges’

from inpatient services in the Assuring Transformation dataset for two periods

of time; a year from October 2015 to September 2016, and a year from October

2016 to September 2017. It’s also one of the most complicated graphs in this

series, so I’ll go through it in a bit of detail.

The first thing to say is that overall the number of people ‘transferred’

from inpatient services has increased, from 2,050 people in 2015/16 to 2,235

people in 2016/17.

Of the people who have been ‘discharged’, in 2016/17 almost

a quarter of people (525 people; 24%) moved to independent living or supported

housing. Another fifth of people (450 people; 20%) moved to their family home

with support, making nearly half of everyone ‘transferred’ from inpatient

services.

Where did everyone else go? For over a sixth of people in

2016/17 (375 people; 17%) their ‘discharge’ was actually a transfer to another

inpatient unit, confirming the picture of ‘churn’ of people passed around inpatient

services found elsewhere in this series. Even more people (410 people; 18%)

moved into residential care. Given that some inpatient services have re-registered themselves as residential care homes with the CQC, it is unclear

to what extent people are leaving an inpatient service to move somewhere more

local and homely, moving somewhere very similar to where they were, or not

actually moving at all but staying in a place that has re-registered.

In 2016/17, there were also another 195 people (9%) who

moved to an ‘other’ location – again it is unclear what these ‘other’ places

are, but are they wildly different from where people were moving from? Finally,

120 people (5%) are in the puzzling category of ‘no transfer currently planned’

while having apparently already been transferred.

So in this final post in the series, there are definite

signs that Transforming Care is exerting pressure for more people to have plans

to leave their current inpatient services, and almost half of those people who

are leaving are moving to independent or supported living or back to the family

home. There are also some worries about the feasibility and sustainability of

some of these plans, and the extent to which many people ‘leaving’ inpatient

services are actually leaving for something radically different or being

churned around a system that doesn’t call itself an inpatient service system but

looks mighty similar to the people living within it.

One final point - I started this short series of blogs with a warning from @MarkNeary1 that all these graphs and numbers are people - and then I spent five blogposts talking only about numbers. I hope that numbers (which is what I spend a lot of my working life trying to understand) can give part of the picture and are useful in encouraging change, but I do worry if I'm 'assuring' myself that this the case. I want to leave the final word to a tweet from @nbartzis which sums up the whole issue perfectly.

One final point - I started this short series of blogs with a warning from @MarkNeary1 that all these graphs and numbers are people - and then I spent five blogposts talking only about numbers. I hope that numbers (which is what I spend a lot of my working life trying to understand) can give part of the picture and are useful in encouraging change, but I do worry if I'm 'assuring' myself that this the case. I want to leave the final word to a tweet from @nbartzis which sums up the whole issue perfectly.